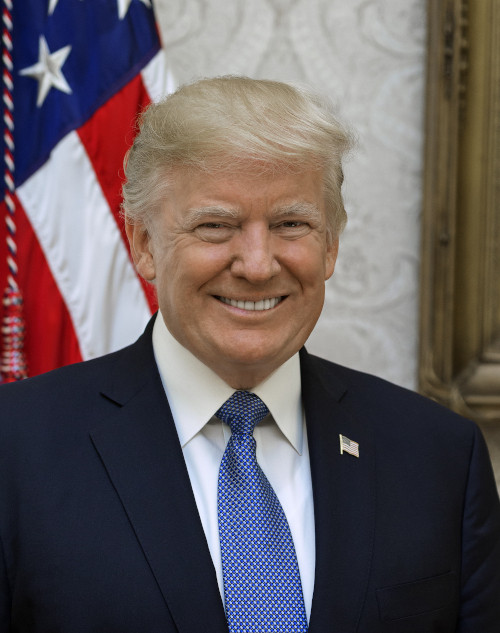

The Weekly: Gone 100 Days of Donald Trump

On Saturday, Donald J Trump will have been President of the United States of America for one hundred days. Since the era of Franklin Roosevelt, this first milestone in a new incumbency has been used by commentators and the public to gauge both the early political and strategic trajectory of a new Presidency and as an opportunity to take stock of how far a new administration has succeeded in fulfilling campaign commitments.

- by Angus Taverner ,

- Friday, 28th April, 2017

On Saturday, Donald J Trump will have been President of the United States of America for one hundred days. Since the era of Franklin Roosevelt, this first milestone in a new incumbency has been used by commentators and the public to gauge both the early political and strategic trajectory of a new Presidency and as an opportunity to take stock of how far a new administration has succeeded in fulfilling campaign commitments.

If President Trump remains true to form, he will be ebullient in celebrating his early successes and dismissive of those who might dare to suggest that he has fallen short on many of his electoral promises: stymied, either by other pillars of the US’ constitution or by his own administration’s shortcomings.

Given the unlikely presidency of Donald Trump, and the challenging nature of the man himself, it seems certain that there will be many fingers pointing to his failures: to impose the ban on Muslim travellers, to compel Mexico to fund the construction of a border wall, to raise protectionist measures against China, and to order US withdrawal from NATO. There will also be much debate over the still stuttering mechanisms of his administration, with many political posts still unfilled, and two high-profile lieutenants either out of post already (Lt Gen Mike Flynn as National Security Advisor) or playing a much-subdued role (Steve Bannon – Chief Strategist).

From whichever perspective you look, President Trump remains a divisive figure – a “Marmite character”, as the English might say – you either love it or loathe it. And to an extent, this is clearly part of his populist political appeal. It is the very commentariat that appears nightly to denigrate Mr Trump that adds to his appeal for many US voters. He is still no Washington insider. Many people across America continue to see him speaking up for their interests, rather than those of a narrow governing elite.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE GCC

So, from the perspective of the GCC, how has the first 100 days played out and what conclusions may be drawn from the early engagement between GCC leaders and the 45th President of the United States?

Overall, most commentators are likely to conclude that the arrival of President Trump is seen to be to the advantage of Gulf interests. While relations with President Obama were always cordial, positive, and even warm at times, there can be no doubt that the GCC was stung by what was seen as American failure to stand by old allies during the height of the Arab Spring. Not only did President Obama refuse to support President Mubarak in his hour of need, he simultaneously gave a strong signal of encouragement to the Muslim Brotherhood that paved the way to the election of Mohamed Morsi.

In contrast, President Trump has been much less equivocal towards the Middle East. He warmly and enthusiastically greeted President al-Sisi of Egypt as his guest at the White House. He also took the opportunity to suggest that his administration is seriously considering following the UAE and Saudi Arabia in proscribing the Muslim Brotherhood as a terrorist organisation. He was equally enthusiastic in welcoming HRH Prince Mohammed bin Salman from Saudi Arabia.

The new President has also been less nuanced concerning the challenges posed by Iran to the region than his predecessor. While Mr Trump has backed away from campaign pledges to rip up the international nuclear agreement with Iran – “a very bad deal” – he remains entirely clear that the US, under his leadership, will continue to regard Iran as adversarial. There seems no chance of President Trump surfacing in Tehran, warmly embracing Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. This means that the GCC can be assured that it will retain US support for efforts to push back against Tehran’s hegemonic ambitions. This is most likely to be to the Gulf coalition’s advantage in Yemen where President Trump has already signalled support for the anticipated coalition strike against the strategically vital, Houthi-held, port of Hodeidah.

Economically, it seems too early to determine whether the campaign protectionist, ‘America First’, Donald Trump will gradually be eclipsed by Donald Trump, international deal maker and business leader. If this is the case, it seems that many of the threats to impose protectionist tariffs and wage a trade war with China, will not transpire. This will be a relief to Gulf leaders as they seek to stimulate fresh growth in their economies and who would not welcome any move that might derail the continuing, if still slow, momentum of recovery in the global economy.

And then there is the phenomenon of Russia. For many US political commentators, it seems ironic that the outcome of the election may have been influenced by Russia to encourage victory for Donald Trump – a man who, on the campaign trail, regularly expressed admiration for President Vladimir Putin, and routinely expressed optimism that new warmth could be encouraged to the benefit of the long-time adversaries. The realities of office has brought about an immediate change of tone, which was compounded, first by Russia’s veto of UN Security Council action against Assad in Syria, and then Moscow’s angry reaction to US retaliatory intervention in Syria.

CONCLUSION

As he completes his first 100 days in the White House, it seems self-evident that President Trump has found the task of leading what is still the world’s only Superpower more challenging and more complicated than he anticipated. As he told Reuters in an interview of Day 99: “I thought being President would be easier.”

However, despite initial concerns over his perceived anti-Muslim sentiments, for the GCC, the arrival of Donald Trump looks to have many more advantages than disadvantages, particularly when viewed through the narrow prism of immediate but pressing concerns. However, the Gulf states are also members of the international community and it seems that there is still a significant risk that Mr Trump’s tendency to act on gut instinct rather than at the end of a process of careful consideration, could lead to an unforeseen crisis – perhaps on the Korean peninsula, perhaps in response to Iranian aggression or perhaps through a piece of economic folly, as Mr Trump strives to satisfy his base support to whom he made too many promises that still look unachievable unless he engages in deliberate economic vandalism.

When Donald Trump stood in front of the Capitol Building to take his oath of office last January, there was real and justified concern that the American people had elected an ill-qualified and unprepared populist to serve in the Oval Office. His first 100 days in that office have arguably revealed a slightly different figure: one who is as constrained by the US Constitution as the founding fathers of America intended. One who seems, albeit slowly, to be recognising the underlying complexity of the many challenges facing the world – of which America is part. And one who recognises that he needs friends, as well as taking on his adversaries. It is in this regard that the GCC is arguably better positioned with the US than has been the case over the recent past.

Angus Taverner

(Director Global Affairs Division) (former)